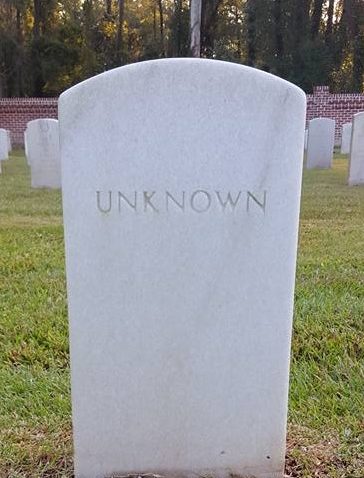

The stone is like the thousands of others around it. It is plain, white marble with a rounded top, the standard issue for the Veterans Administration in national cemeteries. It is flanked by the markers of soldiers that served in World War II and Vietnam in the old part of the Florence National Cemetery. While the others include the name, rank, branch of service, birth, and death dates, this one has only one word: “Unknown”. I can’t think of anything more sad to see on a headstone. No one knows who lies there. I find that very troubling. I’ve been to this cemetery dozens of times, and I’ve visited several other national cemeteries. They are melancholy places, but that one word bothers me. Unknown.

In 2006, I directed the archaeological excavations for the expansion of the Florence National Cemetery. The expansion area was north of the Florence Stockade, a Confederate prisoner of war camp in use from late 1864 until early 1865. Florence is the lesser known twin of Andersonville, the most notorious prison facility of the Civil War. As Sherman’s army swept through Georgia in 1864, Confederate leaders knew the prisoners held at Andersonville had to be moved to a more secure area. Florence was chosen as one place to send prisoners based on the junction of three railroads. The first group of prisoners arrived in September of 1864 before the stockade was even finished.

Once the stockade was completed, the prisoners entered a wasteland surrounded by vertical logs. No provisions for shelter had been made, which left the prisoners to create whatever shelter they could by digging into the ground and using scatter pine boughs and branches, along with blankets or shelter halves if they were lucky enough to still have such things. Pye Branch bisected the stockade, providing drinking water on one end and latrines on the other. Rations were extremely thin, consisting usually of uncooked corn meal and beans. Meat was almost never available and fresh vegetables were basically absent. All of this, combined with a lack of medical support, resulted in the deaths of about 2,300 prisoners by March of 1865 when the stockade was abandoned.

The stockade was guarded by a small group of regular Confederate soldiers supported by South Carolina reservists. The area where we worked in 2006 was the western end of the camp of part of the guard force, probably the 5th Georgia. For an archaeologist, this project was incredible, as we located numerous features and recovered thousands of artifacts. Between the material culture and the in-depth historical research, we made a significant contribution to the historical knowledge of the stockade and those who guarded it.

One of the features which drew our interest had been partially exposed during previous archaeological testing at the site. A backhoe trench revealed the lower portion of a single human burial. As we prepared to conduct the larger excavations, this caused some concern. The historical record indicates that initially, the dead from the stockade were buried in a pit somewhere outside the walls. This pit was said to contain over 400 individuals when burials began in the trenches which spawned the national cemetery. We were concerned the single burial was a sign of a much larger problem.

Our excavations revealed this individual had been buried alone in the bottom of a hut. The Confederate guard had access to timber and other building materials, so some lived in small, semi-subterranean huts. Somehow, this individual had been buried in the floor of one of these huts. The excavation of the remains was conducted by a specialist from the University of Tennessee, who carefully documented the position of each skeletal element and any associated artifacts. Sadly, activities on the property prior to the archaeology destroyed the entire skull. We were able to find two fragments of the cranium many meters away in the backdirt pile. Several buttons were recovered in association with the remains, which indicated that the person was wearing a jacket, possibly military issue. A few pieces of buckshot and a single larger caliber shot were found around the remains. There was no sign of trauma to the bones, so it appears that the shot was there either incidentally or as a complete buck and ball round.

Analysis of the remains provided a lot of information in spite of the loss of the skull. The individual was most likely a young male, aged between 20 and 35 years. He was likely white, although skeletal metrics fell within those of African ancestry as well. He was tall for the time at almost 5′ 11″, with no obvious skeletal abnormalities or disease. Isotopic analysis revealed that his diet consisted of corn products, corn-fed meats, sorghum, and possibly marine foods. This placed his place of residency as the Gulf or Atlantic coasts, which could include South Carolina.

All of this data was great, but what did it really tell us? A young, white male found in the camp strongly suggests that he was a soldier. But this is about all we know. Who was he? Why was he there? How did he come to be buried in that hut and forgotten? Was he sick near the end of the stockade’s occupancy and died, then buried quickly as the guards pulled out of camp? Was he a Confederate soldier trying to get home after the war who took shelter in that hut and never made it out? We don’t know the answer to any of these questions and likely never will. I’ve spent many hours thinking through all of this and I’m no closer to an explanation now than I was in 2006.

After our work was complete, the individual was reburied in the Florence National Cemetery with full military honors. He was interred in a coffin produced for the crew of the CSS Hunley under the careful watch of honor guards representing both Union and Confederate troops. A headstone and a plot were provided for him by the Veterans Administration. It is marked simply “Unknown”. I feel good that I and my colleagues did everything we could to identify him. But it bothers me that we can’t give him a name. He left his family at some point, probably to serve his country. They likely never knew what happened to him. His ancestors have no idea where he is or how he came to be there. That’s terrible and so very sad. Every time I’m in Florence, I stop and pay my respects. I may be the only person who does. It reminds me of the sacrifice made by everyone interred in that sacred space. And it reminds me of all the unanswered questions.

If you have any interest in reading about the work we conducted at Florence, the full technical report is available here. Since 2006, I’ve directed the first professional archaeological research inside the Florence Stockade and the complete mapping of the remains of the Florence Stockade, which are quite impressive! The Friends of the Florence Stockade have worked tirelessly to maintain and interpret the remaining earthworks. If you find yourself headed to Myrtle Beach or down I-95, take a few minutes and stop in Florence to see the stockade. It’s worth it!